It’s a strange thing when travelling abroad, the uncanny and unfamiliar makes itself apparent in curious ways. My first of these culture shocks was a few minutes after boarding my Korean Airlines flight to Incheon, a neighbouring port city to the capital Seoul. It was my first introduction to something I noticed throughout my trip: a widely held Korean commitment to making all media as entertaining and polished as possible. In this case, the aeroplane safety announcements were presented with the glamour and style of a superbowl halftime show. We’re not talking overworked and under-slept RyanAir hosts dragging out a tired life-vest into the aisle with the solemn exhaustion of a school dinner lady. Oh no. Instead, I was treated to a slick music video playing on our screens, where airbrushed K-pop stars lept around in tightly choreographed dance routines, lip syncing effortlessly as they reminded us to tighten our seatbelts. The high camp sincerity and deep bizarreness of it all nearly made me burst out laughing, but all my fellow passengers seemed to find the whole thing totally normal. I’d soon understand why.

After a surprisingly peaceful 14 hour flight, I was awoken to a hot bowl of rice porridge and an absolute treat out of the window. It was at this moment I realised I really was on the other side of the world. From above the landscape looked utterly alien – endless jutting hills and steep peaks bathed in greenery, with the flat patchwork of English fields firmly behind me. Giddily disembarking , I was already bracing myself for the wet-hot Korean summer heat, which barely dipped below 30 degrees for the next few weeks.

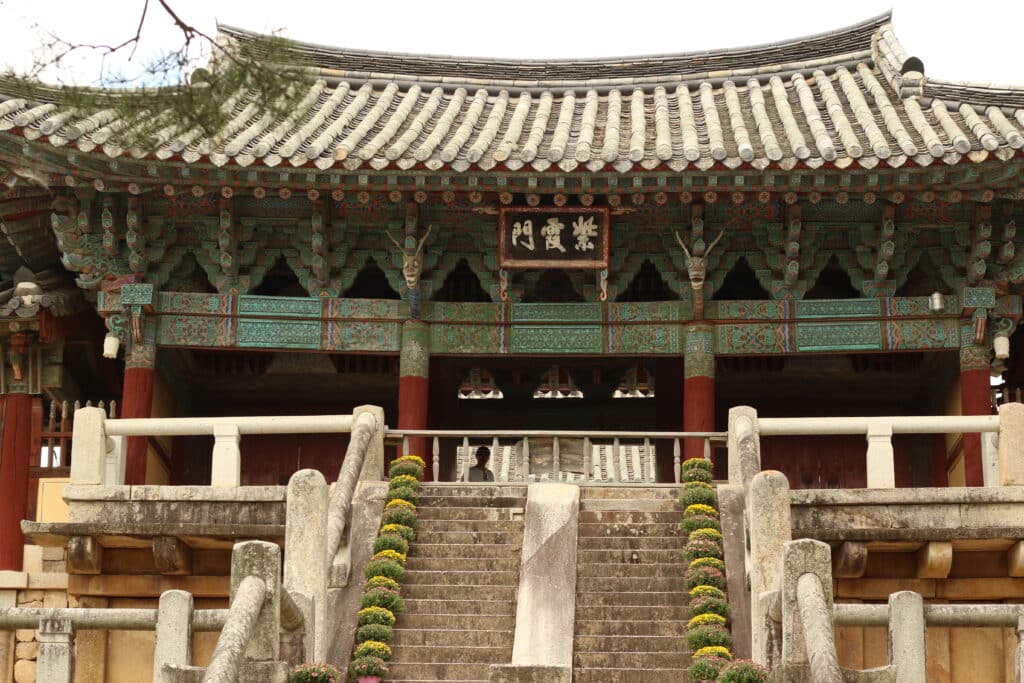

Rather than over-commit my days to a strict schedule of sight seeing, I instead brought a ‘discover Seoul’ pass to get discounted transport and targeted a handful of key attractions each day. I made sure to savour every second of gazing out of bus windows and challenged myself to try something new for every meal (a culinary boundlessness I would come to regret). Despite being more drawn to modern Korean history than its ancient legacy, I’m glad I took the time to visit as many of the traditional palaces scattered round the capital city as I could. On one particularly brilliant evening I found myself quite emotional at how calm and safe I felt so far from home, swinging my legs from the cool steps of Deoksugung Palace while the overripe sunset lit up the slanting roof above me in a rich golden glow.

The next day I decided to put my Korean horror film affection to the test, by booking a ticket to go and see a movie at one of the many astoundingly large cinema complexes in Seoul. I knew of course there was no hope of me understanding the plot, so my criteria for selection was pretty basic: something gory, something silly, something fun. I picked the movie with the highest age certification rating that was showing, and took a moment to lower my expectations. The usual scramble for popcorn was somewhat complicated by attempts to translate the cinema food court menu, which in fact featured squid as the moviegoing snack of choice. The film itself was a riot, and I just about managed to extrapolate the plot on the basis of a smattering of gory murder scenes, car chases, and cyber crime.

After exploring Seouls’ luscious parks, towering shopping complexes and winding cultural museums, I became increasingly struck by the realisation of just how little the complex and recent military and political turbulence of the country was felt at all here. South Korea is still at war with its Northern brother, the two countries only divided a lifetime ago.There was a curious selective amnesia about the deeply traumatic turn of events in the past century that I couldn’t quite shake, and increasingly felt the need to quietly investigate.

My first serious attempt to do so was at the strikingly named Museum of Japanese Colonial History in Korea. The site had only opened in 2018, and I was struck by how low the footfall was in this small but densely filled building, way out of the main tourist centres. All the plaques and exhibitions were in Korean, so it took a whole afternoon of working round with Google translate to read everything properly, but I felt increasingly committed to doing so. It became apparent to me the Museum wasn’t just a testament to the past, but a protest in the present – an artfully constructed demand to Koreans to stay angry about the legacies of injustice, whose memory slips further away with each generation.

The next day I sought to expand my historically minded exploration of Korea, and ventured out to Independence Park and. the Seodaemun prison hall – a former penitentiary during the Japanese colonial period and subsequent years of dictatorship, infamous for locking away and torturing political prisoners and resistance fighters in utterly barbaric conditions.

While waiting for a bus back from Independence Park, I noted again that exercise and fitness seems to be a near constant preoccupation for many locals. When I was sitting down at the bench to catch my breath in the sweltering heat, a 70 year old man on the bench next to me was doing squats. I avoided eye contact, out of both politeness and embarrassment, but like the elderly ladies jogging past he seemed content and deeply unbothered.

On the journey back to my hostel, I took a moment to reflect that the only thing that outranks the elderly in the hierarchy of social sanctimony in Korea is the bus timetable. If a bus in Korea says it is 4 minutes away, it is because it is exactly 4 minutes 0 seconds 0 nanoseconds from your location and hurtling towards you at a relentless speed. In my last few days in Seoul, I skipped nimbly around the cross-hatched subway system and visited as many museums and sights as I could, trying to make the most of my time in this utterly unique metropolis. I spent the best part of a day wandering round the stunning constructed national museum, brimming with exhibits from across the world. They indicated to me that my fascination as a foreigner with Korean culture was eagerly mirrored. It did dampen my spirit just a little though, to walk into the first room of a national museum documenting Korea’s own history, and see the very first pile of exhibits were books written in English by American anthropologists in the 19th century. I was struck that even in the heart of the country’s national museum, American voices and language and perspective were still the dominant framing for Korean history, rather than Koreans themselves. I felt quietly humbled by many moments in Korea, and left feeling like no matter how much I study or read, there might just be some elements of international politics that are just too heavy for me to fully understand.

Looking back, South Korea was a country of relentless pace – of blaring screens and beeping devices, of strict punctuality in everything from the bus timetable to the instant ramen. The rapid metabolism of technical development and social change had given me whiplash in just my few weeks of visit; god knows how it must feel for an older generation of Koreans, living through the rise and fall of empires, in a country lurching forward at the front of history for so long. My favourite moments in my travels had been the quiet pauses for breath. Exploring the garden temples of Seoul at night-time, hiking to the summit of a rural temple, perching on the steps and looking out as miles of crested greenery stretched out into the horizon. These are images I’ll treasure forever.

After returning to the UK late on Friday night, I spent Saturday re-packing my bag: I was moving to London. After years of dutiful library sessions and late-night essay cramming, of formal hall dinners under candlelight and pandemic strolls under moonlight, I’d finally graduated and left Cambridge for good. Who would have thought that my proper goodbye to these seminal years of my life wouldn’t happen on Cambridge cobbles, but thousands of miles away, in the lush forests and urban metropolis of beautiful Korea.